Cruising the West Coast of Vancouver Island by M. Wylie Blanchet.

Cruising the West Coast of Vancouver Island

By M. Wylie Blanchet

Published in Rudder Magazine of December 1936

Is cruising the West Coast of Vancouver Island feasible for the small cruiser? “Quite feasible,” I thought, when I examined the charts a few years ago in search of new waters. “Quite feasible,” I continued to think, after discussing it with various fishermen who knew that coast. And now, after making the trip last summer, I know that it is not only quite feasible but also decidedly worth while.

The West Coast of Vancouver Island has a bad name for wind, fog, and rain, as well as for the vague dangers which people attach to an open seacoast—which is probably why the trip is not more often made. But we found that wind can be avoided by travelling at the proper time of the day; or not travelling at all if conditions are not favourable. It is not by any means all open seacoast, there being miles of inlet waters which one can enjoy while waiting for calmer weather to make an open stretch. Fog can be prepared for by having a working knowledge of piloting, and never neglecting to lay a compass course, no matter how clear the weather may look. And rain, according to the local people, is not usual in July and August. As for the vague dangers, they are no doubt there but with a reliable engine and due precautions they will probably remain vague—and no one could ask for more than that.

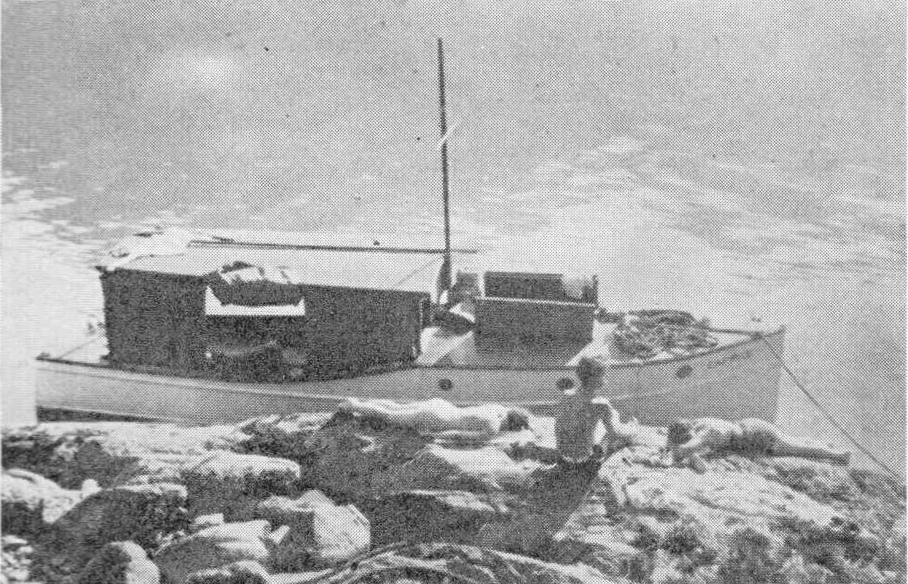

Almost any boat would be better suited for the trip than mine. The engine, 20 hp., was reliable, but the boat itself was hardly ocean going. She was only twenty-five feet by six feet six inches and two feet six inches freeboard aft. Very light timbers and half-inch cedar planking. Decks so light that, when she pitched and rolled in a steep sea, her deck boards rippled underneath the canvas. No, she was hardly ocean going. As for accommodation, there was a double bunk up for’d in the engine room. Otherwise our party of five slept, cooked, ate and lived for a month in the covered cockpit, protected only by canvas curtains.

Tanks full, and all the forgotten things remembered and on board; you leave Victoria and head out the Straits of San Juan (Strait of Juan de Fuca), setting your course to clear Race Rocks. It is possible to go inside Bentinct Island but the pass is choked with kelp and the currents are bad and it might be inviting trouble at the outset of the trip to attempt it. Race Rocks astern, you head in for Beecher Bay, which is about fifteen miles from Victoria and is the first night’s anchorage.

Proper charts of a decent scale will of course be carried, but occasional directions for anchorages for a small boat will not be scorned. The charts do not give close-in soundings of the smaller coves and the Pilot book assumes that you are on a man-of-war and describes anchorages accordingly. Also, something you will soon learn—on the West Coast, an anchorage to be a good anchorage has to be out of the swell.

Keep to the starboard as you enter Beecher Bay and there is good anchorage in a small cove on the east side of Wolf Island. Or if the weather looks settled, instead of entering the bay, cross over to the west side, where just inside the point there is a booming-ground. There you can tie up to the booms or piles; be in a better place to watch the weather out in the Straits and yet have good shelter from everything but a southeaster. If this seems a short run for the first day, it gives time for the shaking down and stowing away usually necessary the first day out. And the main thing is—you are ready for an early start the next morning.

It seems to be absolutely necessary for a small boat, when running the open coast, to travel between two a.m. And ten a.m. At about eight o’clock every morning, the west wind comes up and blows until dusk. It does not take very long for a sea to get up out there, and you must make it a rule to always know ahead where you can get shelter before ten o’clock in the morning, or, better still, eight o’clock. About the only time that we ignored this very good rule, although we escaped any trouble, we were told in no uncertain tones by the local people who know their coast that we were travelling at a very peculiar time of the day for a small boat. There are occasional calms, as we found later, but they are very unusual and are not to be looked for.

Port San Juan, thirty-five miles away, is your next stop and there is no shelter between. Therefore don’t leave Beecher Bay unless the glass is steady and the weather looks good and leave not later than three a.m. Points, such as Sherringham Point and Point-no-Point, which would afford some protection on the inside coast, afford none out there. So don’t be tempted, as we were, to put in for possible shelter behind a probable boom at Point-no-Point. Being new to the West Coast, we were late leaving Beecher Bay and by the time we reached Sherringham Point we had to decide between turning back or finding shelter. A boom at Point-no-Point looked possible, so we tied up behind it. The swell increased with the wind. We soon decided that the point had been well named, probably by some experienced person, for the swells didn’t know it existed. As for the boom, it was tied in such a way that it was free to rush twelve feet in any direction, up and down included, in as many seconds. We were soon obliged to land, and everyone had to spend the night on the beach. But sand-skippers that prefer your sleeping bag to the sand, a steady drizzle and the roar and pound of the surf as well as the anxiety about the boat did not make a restful night.

We turned out thankfully at dawn, only to find that it needs practice to take off from a beach with the swell running and keep either yourself or your bed-roll dry. The dinghy had turned completely upside down a couple of times, before we discovered how it should be done. We left Point-no-Point experienced in several ways.

So I repeat—there is no shelter in between and the buoy at the entrance to Port San Juan should be on your starboard not later than ten a.m. And eyeing Cape Flattery across the Straits, perhaps with faint misgivings for tomorrow, you go out beyond it, you turn into the broad bay to seek shelter and sleep up the Gordon River.

The entrance to the river is on your port hand, in the extreme left-hand corner of the bay. There is a bar across the entrance, but unless a swell is running , there is plenty of water at half-tide for a boat drawing three or four feet.

Follow up the channel to the right and you will find a logging camp and booms to tie up to. Port Renfrew on the northeast side of the bay offers no protection from the swell. There is a post office and small store there, but there is no gas anywhere in Port San Juan. We counted on getting some there but could not, and when we reached Bamfield, we had in our tank exactly one gallon of gas!

This seems a good place to mention gas consumption and speed. On the inside coast I made eight or nine knots and got about ten miles to the gallon. On the West Coast I made only five or six knots and used twice the amount of gas. The long swell cuts down the speed and the angle that the boat is at half the time requires a richer mixture.

Leaving Port San Juan at three a.m., Bamfield, forty-five miles away, in Barkley Sound, is your next objective—no shelter in between and your first cape, Cape Beal, has to be rounded.

It is customary, or rather it became our custom, to celebrate when we had rounded a cape—special eats, a specially strong brew of coffee, and a special brand of Turkish cigarettes kept for these occasions. Also, there is a special feeling that goes with them—you’ll recognize it when you feel it. Further up the coast it took us two weeks to get around one cape. There was nothing very much left to celebrate with by that time—but the special feeling was particularly noticeable. However, that was much further up…..and Cape Beal is what you are worrying about at present.

Give the Cape a wide berth, although I do not think that you will need to be urged after you have seen a big swell break on a reef. You may have cruised for many years on the miles of inside waters of British Columbia. Have crossed the Gulf many times; run the yucultas; or bucked a head wind down Knight Inlet and considered it all in a day’s run. But it takes time to get used to the very different aspect and conditions of the outside coast. There is the unusual motion as the boat rises and falls on the ground swell; the roar and pound of the surf on the rocky shore; the unexpected break and spout of a hidden reef, spray flung high in the air—all presenting to unaccustomed eyes a scene of wild storm and danger. Only after a time do you realize that there is no wind; that it is calm; that it is just the ocean, and that your only danger at the moment lies in keeping too close to the shore.

As you approach the Cape with its lighthouse, the great, white spouts of spray on the surrounding reefs seem to extend for miles ahead; right across the entrance at Barkley Sound—it seems particularly hard to judge their position and distance. But as you gradually work around , keeping well out, they draw in fairly close to the point and you find that you are, after all, outside of everything. It is quite a long run from the lighthouse, up Barkley Sound to Bamfield. But with the long ocean swell first on your quarter and then astern, the Cape behind you and a second breakfast ahead of you—all is well.

At Bamfield, where the Pacific Cable Station is, you fill up with gas and necessary provisions. We did not stay there, but later in the morning made our way over to Ucluelet on the west side of the Sound. It was rather foggy so we could see very little, but I should imagine that Barkley Sound itself would make delightful cruising ground for a couple of weeks, if one did not have the time nor inclination to go further.

Ucluelet, which is a fishing centre, has a store and gas. You can tie up for the night at the main floats, but if you go right up to the end of the Arm there is a wharf and float and more privacy. Also, a trail leads from that wharf over to Wreck Bay, which is a continuation of the much talked of Long Beach. The trail itself is delightful, especially where it comes out on the edge of a cliff at the open Pacific, and the path winds down the slope to the hard, sand beach below.

But lazy, sunny days on the hot sands, surf-bathing and late morning sleeps must end. Once more you pull on your clothes in the semi-darkness, swallow a cup of hot coffee and slice of bread and dawn finds you pulling out of Ucluelet. However, it is cheering to know that the capes on this run are mere points, and provided you make an early start, are hardly worth mentioning.

After passing Amphitrite Light, you will presently have the chance to see how Wreck Bay and Long Beach look from seawards. In the cold morning light, with the long line of white breakers on their grey sands, they will perhaps not look quite so inviting as from shore. In any case, don’t try to look too closely. Our engine stopped just off Long Beach…….There were cruel, jagged reefs not far off, and I would have given a lot to have had an extra half-mile between them and the boat. But someone played the mouth organ—the engine started—and we went on. There is a light on the west side of Templar Channel in Clayoquot Sound. Pass it on your port and from there a run of perhaps five miles brings you to Tofino. Once more you gas up and get supplies.

It might be as well to say something here about supplies. We found it hard to get fresh vegetables. Meat of a kind, you might be able to get on boat day. We didn’t try to; we had bacon and tinned meats on board and otherwise ate fish. Bread was our chief trouble, as we had no oven. We found we could never be sure of getting it, any place. However, on several occasions the local people baked for us. They are all so friendly and interested in seeing people, that I think bread could always be arranged for. For instance, after leaving Tofino, where we unable to get bread, we spent the night at Matilda Creek on the north side of Flores Island. There the telegraph operator telegraphed ahead to Refuge Cove and asked them to bake some bread for us, which we picked up the next day.

There are endless things of interest in all these inlets which I have not got space to describe in this article. But whatever else you do in Clayquot Sound, as you leave by way of Sidney Inlet, plan to spend the day as well as the last night in Refuge Cove (now known as Hot Springs Cove). For at Refuge Cove there is a hot-spring! And not just a hot-spring, but a whole hot waterfall! Reached by a lovely trail through the woods, and surrounded by almost tropical growth, it has an unspoiled setting close to the sea that would be hard to equal. There with a cake of soap beneath the falls, and no desire for anything more, you will soon be babbling that, “This wilderness were Paradise enow.” (Note—tie piece of string to soap.)

Refuge Cove has a fish buyer and a gas barge, and usually fills up with fish boats at night. They are a friendly crowd, and much comforting information re weather and anchorages can be got from them. They will probably tell you that Estevan Point, your next Cape, is one of the nastiest on the coast. And you will get out your charts and they will show you this or that. And then you will go back to your boat and give your engine the once-over before turning in.

The first signs of light will just be showing, when you weigh anchor and slip out the entrance. The fish boats will already have gone out, but will probably be poles down on the horizon—the sea will be deserted and you must make your Cape alone. It is almost two hours run out to the Point. If, when you get there, you have any doubts about the weather, put back into Hesquiat Harbour and don’t try to make it. For after you round the Cape, there is a long run on a lee shore broadside to the swells, before you can get shelter at Friendly Cove, in Nootka Sound.

Friendly Cove, of early history, is around inside the lighthouse. There you can see where the early explorers built the first (non-indigenous) boat to be launched on this coast, on the land given them by the Indian Chief, Maquinna.

Gassing up at Nootka, you have a quiet day’s run up through the Tahsis Canal, and Ocean and Capes seem very far away. We spent that night tied up to a boom just the other side of Hecate Channel. The next morning we ran over to the C.P.C. Reduction Plant, where we loaded up with more gas and provisions. We found good anchorage for the night in Queen’s Cove, on the north west side of Esperanza Inlet. There we were out of the swell and the water was warm enough to enjoy swimming.

We left next morning for Kyuquot Sound, but when we got outside, we did not like the appearance of the weather, so put in behind the sand-spit on the inside of Catala Island and anchored for the day. It is one of the most pleasant memories of the trip. In the morning we explored various caves that are worn deep into the cliffs by the waves. In the afternoon we rowed part of the way and then walked at low tide around to the outside of the island. The sea-life and growth were varied and strange, every pool was an aquarium. The kelp was quite different from the inside coast, being very wrinkled or corrugated, and with many small floats instead of one big one. There were goose necked barnacles, from which the ancient mariners believed a certain species of goose were hatched. Abalones, on the pink-hued rocks below very low tide. These are good eating, but it would take a strong stomach to tackle anything as virile-looking as a live abalone. The sea anemones were pale green and most intelligent. We fed them bits of mussel and crab, which they engulfed gratefully; but when we fed them stones, they spat them out again; and we thought of Mrs. Be-Done-by-as-you-Did, and wished we hadn’t. On the outside of the island, a great pebbly beach, fifty feet wide with a grade of about forty degrees, lies exposed to the open Pacific. I shall always regret that we could not have watched a storm from Catala Island.

It was almost calm in the evening and we were half tempted to make the run to Kyuquot before dark, but decided against it. A little later a very old Indian and his equally old wife paddled past our anchored boat.

“Where you going?” the old man asked.

“Kyuquot, in the morning,” we replied.

“Huh, me go Kyuquot now.” He made no other comment and they passed on soon disappearing in the dusk—an all-night paddle to Kyuquot, the Place Of Wind. But I think the old Indian knew his weather, and later we wished that we had followed their example.

As usual we got up early and were not sorry to, as it rolled all night. But the wind got up early too, and by the time we had passed Tachu Point it was uncomfortably rough. The water at the Point itself was very confused and to go back seemed worse than keeping on. We had been told that once we passed Tachu Point that there was a passage inside the reefs. But it was misty inshore and breaking heavily on the reefs and we did not dare risk trying to find the passage. I do not think it was more than fifteen miles, but it took us more than four hours to make the the red buoy at the entrance to Kyuquot. We had to run in broadside to the waves and someone had to warn the helmsman when the larger waves were coming so that he could head up into them or run off before them. This brought us uncomfortably near reefs at times, but we finally worked our way in behind Union Island. It was our last trip outside for two weeks!

The stores, gas, fish buyers, etc. At Kyuquot are rather hard to find. They are behind a cluster of small islands over against the mainland and north of Union Island. A great collection of fish boats tie up at Kyuquot every night, and with the Indian dugouts from the village paddling to and fro across the harbour, it is rather picturesque. There is no more gas, etc. Until you get to Quatsino Sound and if there happened to be no gas barge in Winter Harbour you would have to run up the Sound to Port Alice, which is twenty-five miles further.

When you are ready to leave Kyuquot, ask the fishermen and they will show you the passage inside the reefs; which will give you fairly good protection on your way over to Nasparti.

“Why Nasparti?” you may ask, as it seems miles out of your way. But it is Nasparti because Cape Cook, like Mount Everest, needs a base as close to the final assault as you can get. You do not go up Nasparti itself, but follow along the shore of Brooks Peninsula until you come to Pedlars Bay. There, on the north side of the small island that lies in front, you will find a safe anchorage, and probably three or four fish boats.

You, I hope, will have normal weather and be off at two the next morning. We had two weeks of lovely, hot, sunny weather—but it blew steadily night and day. In our sheltered corner and along all Brooks Peninsula, it was impossible to tell what the weather was like outside—you had to run out to the Cape itself. Five mornings we got up in the dark and ran the six miles out to the Cape. Only to find a long, white line of breakers extending for miles off Cape Cook, where the west wind, that had blown all night, met the tide.

The fifth time we went out we attempted it; we were beginning to be rather sensitive about it. But a tide rip soon knocks that out of you. The waves were high and green, with scant space between them and they ran counter to the swell. The engine stopped once, our hearts with it……both started again. Should we or shouldn’t we? And then our bilge-pump broke and decided for us. So, with Solander Island just in sight, we had to turn back.

It was foolish to have attempted it, in our boat. Even the fish boats with their sail to steady them, fished only for a few hours a day in those two weeks and then came in for shelter.

“Smoking white out there,” they would report when they came in. And we would resign ourselves to further waiting. Not that it was hard to pass the time. We explored an ancient Indian village and found its burial island with dozens of their old high-prowed dugouts drawn just above high tide mark. Some contained the bones of their owner. Others, the old cedar boxes with the dead owner’s personal effects. Then we fell in with a party of hydrographers and spent many pleasant evenings with them around the big fire at their camp.

Finally, came the calm—as unusual as the two weeks blow. At nine o’clock one morning, while we were enjoying a leisurely breakfast, a fisherman, who was anchored near us—a friend of almost two weeks now—called out that they thought a change had come and that they were going to try and make Klashkisk; did we want to come along? Did we!

We had five or six fish boats as escorts—most reassuring. We reached the Cape; it was almost flat calm. With bewildering ease we made our Parnassus—admired the sea lion colony on Solander Island—and wandered into Klashkish, with one of the fish boats, for lunch. It was still flat calm in the afternoon, so we ran on to Winter Harbour in Quotsino Sound.

Early the next morning we ran out to just this side of Cape Scott, planing to spend the night in one of the several places out near the Cape where there is good shelter, if the calm did not hold. Get a fisherman to mark these for you. You may need them, as Cape Scott has to be rounded at slack-tide on account of the tide rips and Nahwitti Bar off Bull Harbour has to be crossed at slack unless there is a small tide.

At Cape Scott itself, we found a Danish farmer and his big family farming in the middle of the sand-dunes that stretch from one side of the Cape to the other. There we got green vegetables, fresh eggs, butter and cheese and homemade bread and promptly celebrated all the Capes over again. The farmer showed us a collection of glass floats for fishing nets, some as big as pumpkins, which he said had drifted across the ocean from Japan. And he told us the funny story of a German fisherman who firmly believed that they grew on a certain kind of tree up in the Queen Charlotte Islands.

At four in the afternoon we rounded Cape Scott: Triangle Island showing up now and then in the fog bank that lies like a great continent about ten miles off the coast. In about an hour’s time we found ourselves in the middle of the fishing fleet out from Bull Harbour, which is a fishing centre on an island just around the northern point of the East Coast of Vancouver Island. It was still flat calm but there was a big swell. One minute the boats would be in sight and then we would be in the trough and the sea would be empty.

More boats; appearing and disappearing; up and down. We looked back, but Cape Scott had already faded out of sight. And then we realized with a strange lost feeling that, that night in Bull Harbour we should be celebrating our last Cape—the trip over as far as the West Coast was concerned.

-

External Links

- Sorry, no links have been posted